Harold Neal and Detroit African American Artists: 1945 through the Black Arts Movement explores the efflorescence of Detroit African American art in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, as artists responded to the Civil Rights, Black Power, and Black Arts Movements. This vibrant art scene rivaled that of New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. The exhibition focuses on Harold Neal, who created some of the most forceful artistic statements of the era. It also features Neal’s predecessors, Hughie Lee Smith and Oliver LaGrone; his contemporaries, Glanton Dowdell, Jon Lockard, Henri King, LeRoy Foster and Shirley Woodson; and his successors Aaron Ibn Pori Pitts and Allie McGhee. These artists, in general, felt that art should speak directly to the experience of Black Americans using African American figurative subjects.

Harold Neal

Title unknown, date unknown

Oil on board

Neal family collection. Detroit

Artistic Training

Harold Neal, Hughie Lee-Smith, Glanton Dowdell, LeRoy Foster, Henri King, and Charles McGee all studied at Detroit’s Society of Arts and Crafts (SAC, now College for Creative Studies). Unlike its competitor, Meinzinger’s art school, SAC welcomed African American students, many of whom, like Neal, paid their tuition with World War II’s GI bill. Training at SAC was grounded in life drawing.

Harold Neal

[Life drawing], Sketchbook, 1948-1953/54

Red chalk on paper

Harold Neal

[Society of Arts and Crafts students], Sketchbook,

1948-1953/54

Graphite on paper

Harold Neal

[Trumpet and masks], Sketchbook, 1948-1953/54

Watercolor on paper

Sketchbooks: Neal family collection, Detroit

Harold Neal

[Still-life], 1950

Oil on board

Chinyere Neale, Detroit

SAC teachers Sarkis Sarkisian and Guy Palazzola favored applying numerous thin layers of paint, which revealed the work’s under layers.

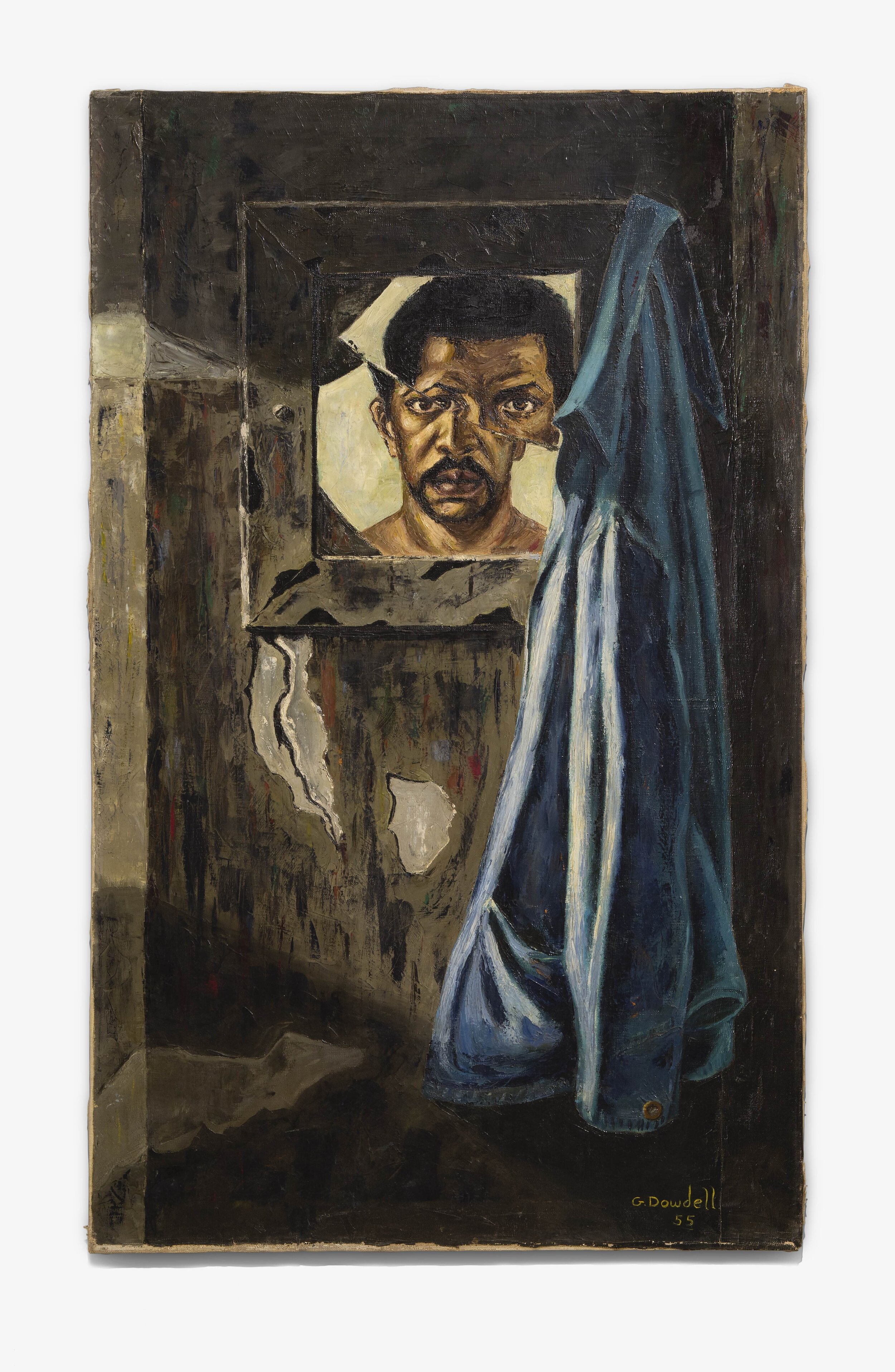

Glanton Dowdell

Southeast Corner of my Cell, 1955

Oil on canvas

Donnell Walker, Yeadon, PA

Neal’s time at SAC was sadly marred by the imprisonment of his good friend Glanton Dowdell for an incident that may have happened at a drunken art students’ party. Dowdell continued to paint in prison. This painting was clearly influenced by Cubism.

Early Work

Harold Neal

Title unknown, before 1958

Oil on board

Neal family collection, Detroit

Harold Neal

Title unknown, 1957

Oil on board

David and Linda Whitaker, Detroit

Harold Neal

Status Seekers, 1963

Oil on illustration board

Shirley and Darnell Kaigler, Detroit, MI

Neal was influenced by the surrealist style of Hughie Lee-Smith, such as his depiction of inexplicable poles and balloons in his image of young girl, 1957, and in his Status Seekers, 1963. Status Seekers and Neal’s painting of a man with a balance (at the beginning of the exhibition), as well as Charles McGee’s Mask, c. 1962 and Jon Lockard’s If I Were Jehovah (later in the exhibition) refer to Paul Laurence Dunbar’s c. 1895 poem “We Wear the Mask,” which poignantly describes the lives of Black people in America.

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,--

This debt we pay to human guile

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

Why should the world be over-wise,

In counting all our tears and sighs?

Nay, let them only see us, while

We wear the mask.

We smile, but oh, great Christ, our cries

To thee from tortured souls arise.

We sing, but oh the clay is vile

Beneath our feet, and the long mile,

But let the world dream otherwise,

We wear the mask!

Hughie Lee-Smith

Title unknown, 1955

Pencil on paper

Patricia and Randall Reed, Fraser, MI

Charles McGee

Mask, c. 1962

Charcoal on paper

David and Linda Whitaker, Detroit

“Seeking Respite”

In 1969, at the height of the Black Liberation and Black Arts Movement, Neal wrote that “sometimes in seeking respite” from his anger about discrimination against African Americans, he “explored the beauty of Black women and children. Other times I try to show through paintings of bridges, houses and still life what the human hand is capable of in the brief period between its destructive endeavors.”

Harold Neal

Bethsheba [sic], 1961

Oil on board

Donnell Walker, Yeadon, PA

Oliver LaGrone

Dancer, c. 1957

Bronze

Estate of David E. Robinson, Detroit

This sculpture portrays Pearl Primus, who first brought African dance to America in the 1940s.

Harold Neal

Man Span, 1963

Oil on board

Private collection

Harold Neal

Everyone Loves Saturday Night, 1965

Oil on board

Private collection

An accomplished pool player, Neal felt that playing pool kept him in touch with regular people. “As an artist, your role in society is defined … by those who patronize and support you. … I like the game of pool. It keeps be from being held captive.”

Radicalization: Black Nationalism

Harold Neal was sympathetic to Black Nationalism, which was advocated by Malcolm X. Unlike the integrationist approach of Martin Luther King, Jr., Black Nationalism held that, for the betterment of their people, African Americans should separate themselves from white society and develop their own economy and culture. In the mid-1960s Neal began to create more socially conscience works of art. Reluctant Flowering depicts a 13-year old girl, who, already a prostitute, has become pregnant.

Harold Neal

Reluctant Flowering, 1966

Oil on canvas

Private collection

Radicalization: Black Christian Nationalism

Related to Black Nationalism was Black Christian Nationalism, which was led in Detroit by the charismatic Rev. Alfred Cleage, Jr., pastor of Central Congregational Church (later the Shrine of the Black Madonna). To Cleage, white Christianity was a tool of oppression. Neal, apparently, agreed. His painting of a man with a cross seems to depict a white Jesus bringing the chains of slavery to Blacks. This was, according to some interpretations, sanctioned by the Bible in Ephesians, VI, 5-7: Bonded “servants, be obedient to … your masters …as unto Christ.” Here revenge is sought by a black bird who is gouging out the eye of the white Christ.

Harold Neal

Title unknown, 1966

Oil on board

Neal family collection, Detroit

Jon Onye Lockard

The Black Messiah, c. 1967

Pastel on canvas

Grand Valley State University Collection,

Gift of the Family of Joseph and Mary Stevens

Henri Umbaji King

Sacred Mother and Child, before 1971

Oil on board

Shirley and Darnell Kaigler, Detroit

Rev. Cleage believed that Jesus was Black, due, in his words, “to the historical intermingling of African and Mediterranean races.” African-American parishioners and others were better able to identify with this incarnation of God.

The Black Arts Movement in Detroit

New York poet and playwright LeRoy Jones (later Amiri Baraka) started the Black Arts Movement (BAM) in 1965 following the assassination of Malcolm X. The BAM held that Black art should be about the African American experience, which, adherents felt, was categorically different from that of whites. These ideas premiered in Detroit in 1966 at First Black Arts Conference, organized by Rev. Cleage; bookseller and radical activist Edward Vaughn; and Neal’s friend Glanton Dowdell, who had been released from prison in 1962. The BAM was the artistic branch of the Black Power Movement, initiated in 1966 by Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) chair Stokely Carmichael.

On the visual arts panel of Detroit’s Second Black Arts Conference in 1967, Neal said:

Artists must stop being a specialist [sic] and must be like any other black man fighting for his freedom. … [I] don’t go along with tired white boys who introduce a series of dots one year and are hailed by critics who have to find something new.

Here Neal was referring to the abstract/non-objective art which then dominated the white art world.

In July 1967, shortly after the second conference, the Detroit uprising/rebellion took place and Neal responded.

Harold Neal

Title unknown, 1968

Oil or acrylic on board,

Leslie Atzmon, Ann Arbor, MI

During the 1967 uprising/rebellion, four year-old Tonya Blanding was shot by the National Guard, who mistakenly thought that a person lighting a cigarette was actually firing a gun from her home.

Harold Neal

Title unknown, Riot Series?, 1960s

Oil on board

Private Collection

In this image, the man appears to have been arrested. Neal also explored Black incarceration in his unlocated Attica, c. 1972, which refers to the 1971 uprising in New York’s Attica prison. This surrealistic work depicts a semi-nude white woman, probably an allegorical figure of Injustice, squeezing a Black man’s head and torso in a bizarre contraption

Harold Neal

Brother S.C., 1967

Oil on board

Private collection

This unidentified man sports a beret of the type often worn by urban militants. It is likely to be a home-grown Detroit militant, of which there were many, because the Black Panthers did not come to Detroit until 1968.

Harold Neal

Rag Doll, c. 1967-1969

Lamp black and oil on artist board

Patricia and Randall Reed, Fraser, MI

This work subverts sociological studies from the 1930s and 1940s that suggested, sadly, that African American children preferred white dolls. As noted, Black Nationalism called for Blacks to reject white culture and create their own. Accordingly, this child rips apart his white doll.

Other Black Arts Movement Detroiters

Like Neal, Jon Onye Lockard, Glanton Dowdell, and Neal’s younger friends, Aaron Ibn Pori Pitts and Allie McGhee asserted a Black Arts Movement agenda in their work.

Jon Onye Lockard

If I Were Jehovah, 1970

Conte crayon on paper

Courtesy of the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center, Wilberforce, OH

As noted earlier, this drawing refers to Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem “We Wear the Mask.”

However, here the man does not wear, but furiously rips apart the concealing mask.

Jon Onye Lockard

No More!, 1968-69

Offset lithograph

Leslie Kamil, Ann Arbor, MI

In No More! Lockard spoofs the cheery servant, Aunt Jemima, a pancake maker’s brand that offended many African Americans. He turns her into a Black militant, wearing the black, red, and green of the Black Nationalist flag. The figure bursts the Aunt Jemima stereotype by smashing a Black Power fist through the box. Lockard produced many of his works as multiples, in this case using commercial lithography, because he wanted them to be readily available to people who could not afford high-priced artworks, like oil paintings.

Glanton Dowdell

Untitled, 1975

Oil on canvas

Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, Detroit

In 1967 Dowdell painted the famous Black Madonna and Child in Rev. Cleage’s Central Congregational Church (later the Shrine of the Black Madonna). In this work, he depicts the lynching of three men. He, thus, calls for a reckoning for the endless atrocities inflicted on African Americans.

Aaron Ibn Pori Pitts

Road to Revolution III, 1967

Woodcut, reprinted with hand-coloring, 1991

Linda and David Whitaker, Detroit

Pori Pitts was an early adherent of the Black Arts Movement and a member of the Black Panther party. From 1968 to 1976, he edited and contributed to Black Graphics International, a journal that featured the art and literary works of radical African American artists. Road to Revolution was published in the journal’s first issue. It apparently refers to the Detroit uprising/rebellion of 1967. It features the head of a man with bared teeth and a threatening gesture. Fire in the foreground seems to be his instrument of terror.

With the title Road to Revolution, Pori Pitts implies that the Detroit rebellion and other such urban uprisings of the 1960s were not just spontaneous expressions of rage at white oppression, but a prelude to the overthrow of racist, capitalist rule, a view shared by many Black militants nationally.

Allie McGhee

Cover of Black Graphics International, no. 3, 1969

Offset lithography

Courtesy of Givens Collection of African American Literature

University of Minnesota Libraries, Minneapolis, MN

Allie McGhee, a friend of Aaron Ibn Pori Pitts, also contributed to Black Graphics International. This image depicts a skeleton, Death, wearing a military epaulette. Behind him, another figure tries to flee from Death, yet his hand rests on a large skull. The illustration protests both the Vietnam War and, in McGhee’s words, “the 1960s violence of white against black and black against white.”

Allie McGhee

All Times, 1968

Collage

Collection of the artist, Detroit

This very complicated collage protests the centuries of oppression against Blacks. The central figure is President John F. Kennedy’s wife, Jackie. In the popular imagination, the Kennedy administration (1961-1963) was thought to resemble Camelot, the ideal mythical home of the King Arthur, which was the setting for a contemporary Broadway musical of the same title. But, according to McGhee, reality for most African Americans was at “all times” anything but Camelot. Surrounding Jackie are prominent historical and contemporary Black heroes including Malcolm X, LeRoi Jones [later Amiri Baraka], Aretha Franklin, jazz/blues singer Ethel Waters, and Martin Luther King, Jr. Above the Black Power sign are the letters KKK on a blue sleeve with a white epaulette, implying the known collusion between military/law enforcement and the Ku Klux Klan.

Allie McGhee

Last Oil, 1969

Oil on canvas

Shirley and Darnell Kaigler, Detroit

At this painting’s lower right edge, one can see, in McGhee’s words, a “shrouded figure in black and mask [who] brings the cleansing of fire. A physical and spiritual rebirth.” Flames seem to engulf the rest of the picture. The work may refer to the 1967 Detroit rebellion/uprising with its cleansing fire leading to the birth of a Black City. Allie McGhee had a direct experience of the rebellion. A National Guardsman stuck a bayonet in his ribs when he was out after curfew.

In this work, McGhee melds the artistic approaches of his mentors, Harold Neal, Al Loving and Charles McGee. Neal favored a figural Black Arts Movement aesthetic, whereas, by 1969, McGee and Loving were working in abstract/non-objective styles. This is called Last Oil because later McGhee painted with acrylics.

“Seeking Respite”—Reprise

Not all of the art created by Detroit’s Black Arts Movement artists was specifically political. This became increasingly true in the 1970s. Indeed in 1980, Neal wrote:

The more things change the more they stay the same. I don’t have time to be angry anymore. If you make me always direct my energy toward getting your foot off my neck, then you are oppressing me. … But I can’t carry the burdens of oppression on my shoulders my whole life.

The BAM artists often focused on African American life, culture and heritage. They were particularly interested in portraying historical and contemporary American African heroes and sheroes, including public figures, musicians and actors, among others.

Harold Neal

Checkers, c. 1972-73

Oil on board

DMC, Detroit Receiving Hospital, Detroit

Oliver LaGrone

Sojourner Truth, 1941-1942

Faux bronzed plaster

Roy Robinson, Sparta, MI

Oliver LaGrone

Portrait of George W. Crockett, Jr., 1969

Bronze

Damon J. Keith Collection of African American History

Wayne State University Law School

Born into slavery, Sojourner Truth became an abolitionist and women’s right activist.

George W. Crockett, Jr. had a distinguished career as a champion of leftist causes and Civil Rights. In 1969, he became a hero to Detroit’s black community when he released, for lack of evidence, 140 persons arrested during a bloody confrontation between the Republic of New Africa, a Black Nationalist organization, and the Detroit Police.

Harold Neal

Portrait of Rappin’ Johnson, 1977

Oil on board

Chinyere Neale, Detroit

According to Neal’s daughter Chinyere, Rappin’ Johnson was a “legendary community member, … a kind of unofficial community griot.” A griot, a term adopted in the U.S., was originally a West African elder who passed on communal history orally through stories, poetry, music, etc.

In this work Neal continued to use the style of layering flat, translucent shapes that he had learned at the Society of Arts and Crafts in the 1950s.

LeRoy Foster

Untitled [Portrait of Paul Robeson as Emperor Jones], 1976

Oil or acrylic on board

Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, Detroit

Paul Robeson was a hero to many as an actor, singer, peace and Civil Rights activist. A Communist sympathizer, he was blacklisted during the McCarthy era in the 1950s. On Broadway in 1925, he played Emperor Jones in Eugene O’Neill’s play of the same title. In it, a wily Brutus Jones, formerly a Pullman porter, becomes the vastly wealthy Emperor of an unidentified island. Foster portrays him wearing military garb seated on an extravagant throne, the very picture of O’Neill’s vain autocrat. Charles H. Wright, founder of the Wright Museum, greatly admired Robeson and commissioned Foster to create this and several other images of him.

Henri Umbaji King

Title unknown, undated

Pastel

Claire Neal, Detroit

Harold Neal

Young Trumpeter, c. 1972

Offset lithography

Ira Neal, Evansville, IN

Jazz and Blues, “African American Classical Music,” as Neal called them, were major inspirations for Detroit visual artists. King’s painting may be a portrait of an actual saxophone player, who has not yet been identified, while Neal’s trumpeter embodies the aspirations of many young Black musicians. Neal produced Young Trumpeter as a commercial lithography, because he wanted it to be available to people who could not afford high-priced artworks, like oil paintings.

Shirley Woodson

Martha’s Vandellas, 1969

Oil on linen

Collection of the Artist

The songs of Motown Records swept the country in the 1960s, including Dancing in the Streets by Martha and the Vandellas. In this painting, Martha is accompanied by her backup singers and two styling saxophone players. She is masked in white, like Nigerian Igbo dancers, transforming her into, in Woodson’s words, “personage” or “deity.” This masking gives Martha a ceremonial presence, thus elevating popular music to the level of ritual. This mood is further enhanced by the crowned golden head in the rear, which is painted in the style of ancient Egypt, that is, with head in profile and the eye in frontal view.

Identifying with the African Past

During the 1960s and 1970s, many African Americans began to proudly claim the history and culture of Africa, including Egypt, as their rightful heritage, thus linking themselves to some of the greatest civilizations of the past. Many artists, such as Charles McGee, Henri King, Oliver LaGrone, Jon Lockard, Aaron Ibn Pori Pitts, as well as Shirley Woodson, often referred to Africa in their works.

Allie McGhee

Abu Symbols, 1973

Oil on canvas

DMC, Detroit Receiving Hospital

According to Allie McGhee, “In the 1970s [Black] people were trying to lift themselves up from the idea that they came from nothing to recognize that they were kings and queens, mathematicians, recognize they were something more than slaves.” Abu Symbols makes this point. It is based on the four colossal statues of Pharoah Ramesses II, who ruled from 1297 to 1213 B.C.E., which form the entrance of a temple formerly at Abu Simbel, Egypt. McGhee explicitly makes the connection between people of the African diaspora—including African Americans—and the Pharaohs by giving the statue on the right pronounced lips and a pure black face.

Conclusion

The 1980 election of Ronald Reagan marks the end of a revolutionary era in American life. Indeed, by the mid-1970s the fervor of the Black Nationalist, Black Power, and Black Arts Movement had begun to cool. There were many reasons for this, but in Detroit the 1973 election of Coleman Young, a former labor leader, a socialist, and a Civil Rights activist, gave new hope to Detroit’s Black community.

In the vernacular of the day, Harold Neal and the other artists represented in this exhibition “kept the faith, baby” with their community. Through their work of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, they protested the oppression of Black Americans and celebrated African American heritage, life, and culture.